WASHINGTON, DC – JANUARY 06: Pro-Trump supporters storm the US Capitol following a rally with President Donald Trump on January 6, 2021 in Washington, DC. Trump supporters gathered in the nation’s capital today to protest the ratification of President-elect Joe Biden’s Electoral College victory over President Trump in the 2020 election. (Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images)

By now we’ve all heard that we live in political “bubbles.” As US society becomes increasingly polarized, so too do our social circles and media diets. More to the point, right- and left-wing outlets often report the news so differently that it’s hard to believe they’re describing the same events. And as the people around us, the media, and of course our algorithm-driven internet feeds make the world look so different depending on our politics, we begin to lose our shared reality. In a sense, a liberal and a conservative can look out the same window on the same street and yet see remarkably different things.

But how did we become so isolated and so polarized? And what are the downstream effects of this isolation? Our project aims to address these questions by exploring how shared reality or lack thereof is connected to hate and related emotions, such as contempt or disgust, emotions that lead people to avoid and look down on individuals and out-groups they perceive as inferior. We believe this research will deepen our understanding of contemporary US political life, particularly as we see “issue polarization” being replaced by “affective polarization.” Whereas issue polarization describes a widening opinion gap on a policy or platform, affective (in other words, emotional) polarization describes intensifying emotional distance between rival political groups. As affective polarization increases, members of ideological groups begin to strongly dislike and distrust one another, and often develop a sense of moral superiority towards those on the other side. Because of the volatility and hostility affective polarization creates in our world, it is urgent that we address this issue, which we hope to do by delving deeper into the relationship between emotions and our perceptions of reality.

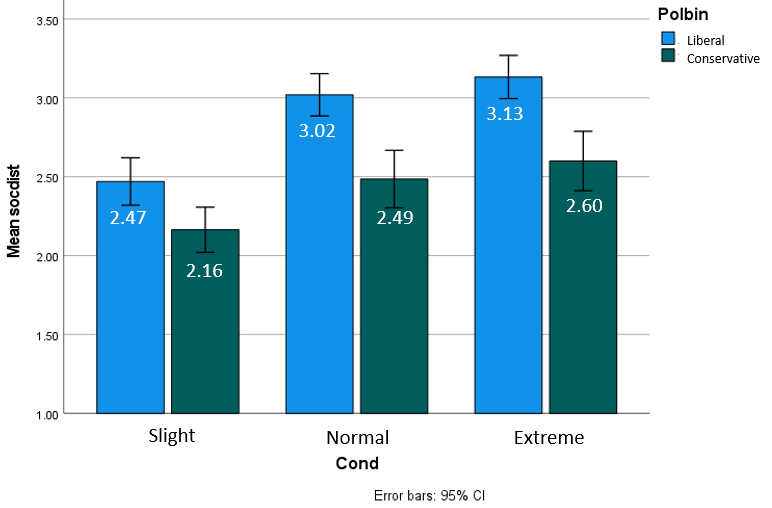

In our first study, we primarily examined the relationship between unshared reality and contempt, which we measured through desire for social distance and self-perceived moral superiority. So far, we have found that as political disagreement increases, shared reality decreases, social distance increases, and moral superiority increases. That is, the further apart two people are politically, the more likely they are to see the world in totally different ways, the less likely they are to want to socialize with one another, and the more likely it becomes that each believes they are a fundamentally better person than their counterpart. Surprisingly, these increases are also more marked between what we consider “slight” vs “moderate” political disagreement compared to “moderate” vs “extreme” disagreement. This would indicate, for example, that a center-left individual would have a bigger reaction to a center-right individual than to a far-right one. We also examined how people perceive the political opinions of someone they disagree with on a given issue. Thus far we have found that the more an individual disagrees with another, the more skewed their understanding of the other person’s views would

In more technical terms, we understand “shared reality” as more than a simple measurement of how closely one’s inner state matches someone else’s. It is, rather, a way of getting at how our fundamental need to get along with and belong among others (what we call the affiliative or relational motive) interacts with the need to believe what others say to reduce uncertainty about the world (what we call the epistemic motive).

For example, if you ask a person with conservative views on immigration what they think the liberal opinion on immigration would be, they are likely to select “The border should be fully open and ICE abolished,” which would actually be a far-left position. In addition, our findings suggest that initial disagreements may erode shared reality faster than later disagreements.

In our preliminary results, US liberals seem to score higher than conservatives overall in terms of social distance and moral superiority. We also find they are more likely than conservatives to misrepresent the other side’s beliefs in a more extreme direction. However, this may stem from the finding that shared reality is generally higher among conservatives. This raises other concerns in and of itself as very high levels of shared reality can allow groups to more effectively carry out anti-social actions. Keeping this in mind, we will continue this work by examining how isolation from perceived out-groups and feelings of moral superiority are related to hate-adjacent processes like dehumanization and support for political violence.

Echterhoff, G., Higgins, E. T., & Levine, J. M. (2009). Shared reality: Experiencing commonality with others’ inner states about the world. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(5), 496-521.

Iyer, A., Jetten, J., & Haslam, S. A. (2012). Sugaring o’er the devil: Moral superiority and group identification help individuals downplay the implications of ingroup rule‐breaking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(2), 141-149.