Breaking the Cycle: Why Jails Could Prevent Hate Crimes Before They Happen

By Lincoln Bohn, M.A.

Published November 26, 2025

James Finney-Conlon, a Jewish public policy professional in Los Angeles, made an unusual choice after antisemitic attacks shook his community: he sat down with the offender. Writing in the Jewish News of Northern California about the experience, Finney-Conlon described watching genuine remorse unfold. The offender had discovered antisemitic conspiracy theories on social media during a difficult period in his life, briefly believed them, and committed a crime that devastated LA’s Jewish community.

This meeting was made possible by REACCH—the Reconciliation Education and Counseling Crimes of Hate program—a pilot initiative by the LA County District Attorney’s office. Instead of prison, hate crime offenders on probation receive counseling, anti-bias education, and victim reconciliation. Finney-Conlon’s experience brought him “a measure of calm and hope,” he wrote, because he saw that change was possible.

But here’s what struck us as researchers: What if we didn’t have to wait until after hate crimes shatter communities?

The Overlooked Opportunity

Hate crime rates in the U.S. have surged to some of the highest levels ever documented, according to recent FBI data. Our response follows a predictable cycle: outrage, prosecution, incarceration, and then nothing. We punish hate crimes after they occur but rarely ask: Could we have prevented this?

This research, funded by the UCLA Initiative to Study Hate, suggests a striking opportunity hidden in plain sight. Studies by criminologist Edward Dunbar and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism have found that between 56% and 66% of hate crime offenders in the United States have previous criminal records before committing their first hate crime. UK criminologists Darrick Jolliffe and David Farrington found rates as high as 97.7%.

This means we already have contact with many future hate crime perpetrators. They’re cycling through our jails, on probation, in diversion programs. The question isn’t whether we can reach them—it’s whether we will.

Research by criminologists Jack McDevitt and Jack Levin found that most hate crime offenders aren’t lifelong extremists but individuals who could respond to intervention if we offered it.

A Public Health Approach to Hate

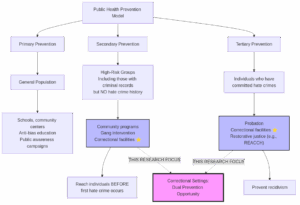

What if we treated hate the way we treat other public health threats—as something that can be interrupted, prevented, and unlearned? The diagram below shows how this framework applies to hate crime prevention:

Figure 1. Public Health Prevention Framework Applied to Hate Crime

Public Health Prevention Framework showing primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention levels. The diagram highlights correctional facilities as serving both secondary prevention (reaching individuals with criminal records before their first hate crime) and tertiary prevention (preventing recidivism among known offenders). This dual prevention opportunity represents the core focus of this research.

Here’s the key insight: correctional facilities offer a unique dual opportunity. For individuals who’ve already committed hate crimes, these settings can provide rehabilitation and prevent recidivism. But for the majority of people in jails and prisons who haven’t yet committed hate crimes—despite sharing demographic and circumstantial similarities with those who do—these same settings could offer anti-bias programming before hate escalates into violence.

This isn’t about expanding incarceration. It’s about harm reduction in spaces where cycles of violence often deepen. Without intervention, researchers like Finney-Conlon note, hate crime offenders in prison may be surrounded by white nationalist groups with the capacity to indoctrinate newcomers into violent extremism.

What Works: Evidence from Around the World

Our team analyzed 25 hate crime prevention programs from around the world—from Norway’s EXIT program that helps people leave neo-Nazi groups to California’s REACCH. What we discovered was encouraging: many of these interventions build on programs already running in correctional settings, like cognitive behavioral therapy and gang intervention models.

Restorative justice approaches, like the one Finney-Conlon experienced, show particular promise. As he wrote, watching an offender confront the harm he caused “brought me a measure of relief and hope to see him seek forgiveness.” But he also asked a critical question: “How many other hate crime offenders are decaying in prison for decades and may likewise feel remorse?”

California’s Window of Opportunity

Los Angeles County is leading the way. In March 2024, the County Board of Supervisors committed to a comprehensive strategy against identity-based hate, coordinating efforts across mental health services, violence prevention, and victim support. The County’s Anti-Racism, Diversity and Inclusion Initiative tracks patterns of hate and discrimination across the region, building the evidence base for intervention.

But a critical gap remains: while communities invest in prevention, individuals cycling through correctional facilities receive little to no hate-specific programming. Our research aims to assess the feasibility of adapting proven international approaches for California’s correctional settings, examining both benefits and implementation challenges.

The convergence of several factors creates an unprecedented opportunity: a reachable population, evidence-based interventions that work internationally, and growing recognition that reactive responses alone are insufficient. The question isn’t whether hate crime can be prevented in correctional settings—international evidence suggests it can. The question is whether we’ll seize this opportunity, or continue responding to hate crimes after they shatter communities like the one James Finney-Conlon worked to heal.

California has the infrastructure, the evidence, and the policy momentum. What we need now is the will to break the cycle.

This research is supported by the UCLA Initiative to Study Hate (ISH). For more information about this ongoing project, contact Lincoln Bohn at Bohnlincoln@ucla.edu.

Bibliography

Dunbar, E., Quinones, J., & Crevecoeur, D. A. (2005). Assessment of Hate Crime Offenders: The Role of Bias Intent in Examining Violence Risk. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 5(1), 1–19.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2025, August). FBI Releases 2024 Reported Crimes in the Nation Statistics [Press Release].

Finney-Conlon, J. (2024, June 5). OPINION | Why I sat down with the antisemite who targeted my community. The Jewish News of Northern California.

Jensen, M., Yates, E., Kane, S., & LaFree, G. (2020). Motivations and characteristics of hate crime offenders. START.

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2020). The criminal careers of those imprisoned for hate crime in the UK. European Journal of Criminology, 17(6), 936–955.

Los Angeles County Anti-Racism, Diversity and Inclusion Initiative. (2024). Preventing and Combatting Identity-Based Hate and Violence in LA County.

Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. (2024). Combatting Identity-Based Hate in Los Angeles County through a Comprehensive, Proactive, and Equitable Strategy [Board Motion].

Los Angeles County District Attorney. (2021, October). Hate Crimes Unit to Launch Restorative Justice Project.

McDevitt, J., Levin, J., & Bennett, S. (2002). Hate Crime Offenders: An Expanded Typology. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 303–317.

________________________________________________________________

This Initiative to Study Hate project examined the feasibility of implementing hate-prevention interventions within California correctional settings. The research focused on identifying the institutional, logistical, and security barriers—as well as the facilitators such as staff support, infrastructure, and community partnerships—that shape the ability to introduce screening tools and rehabilitative programs for individuals at risk of committing hate-motivated offenses. The goal was to generate practical recommendations for adapting and deploying effective hate-prevention strategies in jails and prisons, ultimately reducing hate-related violence and supporting rehabilitative outcomes.

The project was led through the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences / Integrated Substance Use and Addiction Programs (ISAP) by Lincoln Bohn, Dr. Howard Padwa, and Madelyn Cooper.

Lincoln Bohn, M.A., serves as a Research Associate in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His recent engagements include collaborating with the Housing Research Group at California State University, Chico, focusing on studies related to individuals experiencing homelessness. Since joining UCLA’s Integrated Substance Use and Addiction Programs, Lincoln has been involved with a diverse array of subject matter ranging from criminal justice to substance use prevention.